Damian's artistic talent was recognised at school, but convinced by his parents that art was no way to make a living, he enrolled at the University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology to study Applied Biology. By the end of his degree he knew that he didn't want to be a scientist. Science had left him cold, but voluntary work with children with learning disabilities had interested and moved him deeply.

A year behind him academically, I was studying in Edinburgh. We planned to marry when I finished my degree,so for the last year of my studies, Damian moved to Edinburgh, where he was employed to work with learning disabled young adults by Garvald Centre. The following year we married, spent a year in the South of France, returning In 1985 to be residential house-parents for Garvald.

Without Garvald Damian might never have become an artist. At the time we worked there the atmosphere was one of tremendous spirituality, idealism and creativity. People worked astoundingly hard, with incredible devotion and imagination for very modest salaries. A social work enterprise, there were more Art School graduates in the work force than social scientists. Here Damian's innate creativity blossomed, first as a house-parent, then as a teacher. The blossoming ended when he was 'promoted' out of hands on work with young people into a managerial role. He bore this for one unhappy year, at the end of which he enrolled at Edinburgh College of Art.

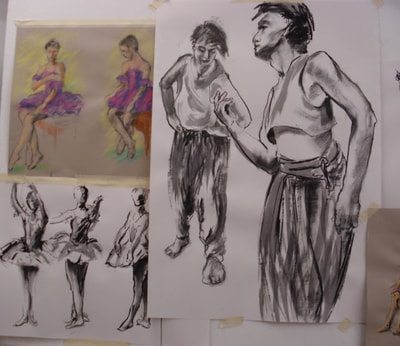

Damian was thirty when he embarked on his degree in Drawing and Painting. It was not easy. Figurative, representational art was not in vogue. He was frustrated by how little teaching there seemed to be on offer and felt he was very much left to get on with his work by himself, work which many of the tutors clearly did not find of interest. However, his degree show sold out and resulted in the offer of a one man show at the Stenton Gallery in East Lothian. That same summer (1995) Damian was awarded the Juliet Gomperts Scholarship to study for two weeks at The Verrocchio Art Centre in Tuscany under the English painter, Oliver Bevan.

Damian cannot stress enough how much he owes this man. Bevan was an extraordinary communicator and role model. He demonstrated, he painted alongside his students; over breakfast, lunch and supper he talked about painting in all its aspects - technical, philosophical, even commercial. He was an enormous inspiration to Damian, who felt Bevan not only taught him to paint, but taught him to teach others how to paint.

On his return from Tuscany, Damian painted for his show in East Lothian, while continuing to work part-time at Garvald. (Something he had done all the way through his degree.) Soon after the show, the first of our four children was on the way.

To my distress, when Isaac was born, Damian wanted to describe himself on the birth certificate as a 'social worker' rather than as an 'artist'. With the responsibility of fatherhood, his parents' conviction that art was no way to make a living was reasserting itself. And then a miracle happened.

A web-site builder (Gavin Bonnar) in the same WASPS building as Damian asked him if he would like to feature on an artists' web-site he was launching. The Internet was then in its infancy (we hardly knew what it was), but Damian said 'Yes'. Shortly afterwards, a young Swede (Peter Leheusen), who had recently inherited his father's shipping company, got in touch. He had seen Damian's work on the web and wanted to commission him to decorate his London flat. Peter was the dream patron: he commissioned copious amounts of work (work for Sweden followed), allowed Damian all the artistic freedom he wanted, paid well and on time. At a critical moment, when Damian might have lost his nerve, Peter enabled him to establish himself as an artist.

The first of our four children arrived in the summer of '97, the second in February '99, the third in February '2001, the fourth in May 2003. Despite Peter's patronage, Damian had not dared give up his part-time Garvald job. This involved evening, weekend and night shifts. With so many babies and small children at home, this was not ideal. Then ECA offered him work as a tutor on their part-time degree course, leading to Damian's giving up social work once and for all.

Damian taught on the part-time degree course for a few years, but eventually stopped. He was particularly troubled by being obliged to participate in a marking system he considered utterly inappropriate. Since then he has been a happy and successful independent teacher (though he does occasionally freelance at the National Gallery) who never awards marks!

It is above all Damian's teaching which has kept the bailiffs from our door. He teaches because it is lucrative, but also because he genuinely likes people, wants to help them and knows from his own experience how valuable a good art teacher can be. Over the years he has taught dozens, probably hundreds of people. Some have become real friends. He enjoys the social contact, he derives real pleasure from his students' progress, but also finds teaching hugely beneficial for his own practice.

I have entitled this piece 'Painting the Pram in the Hallway' (that vehicle and its occupants being considered the traditional enemies of art), but have yet to write directly about Damian's paintings. The paintings in this exhibition depict almost exclusively his family, frequently by the sea, often including cousins and good friends. The fact is that independently of this exhibition, this is what constitutes the bulk of Damian's subject matter.

We brought our children up in a second-floor Edinburgh flat with limited access to a garden.However, Damian's occupation as a self-employed artist and teacher made it possible for us to take the children to the countryside for extended periods of time during the school holidays. We discovered Skipness, Argyll the summer Isaac (our eldest) was born and have been going there twice a year ever since. This is not the height of adventurousness, but we wanted the children to have a place in the country which they knew in depth and where they could run free. Skipness provided this.Our holidays there were (and still are) of necessity inexpensive and simple. We arrive (usually with my sister's family, often with other good friends too) and we guddle there, barely getting into the car until our return home. August in Berneray in the Outer Hebrides is similar.

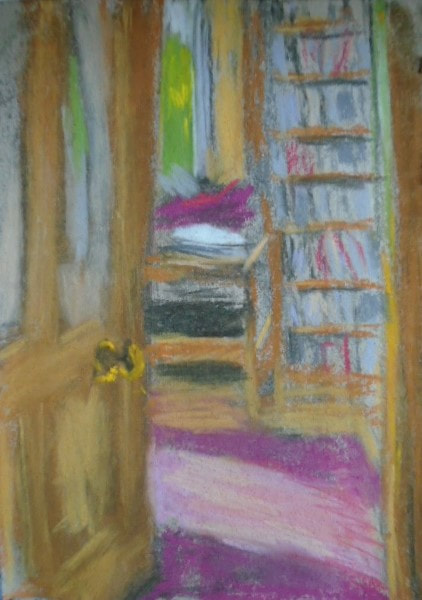

These very simple, highly sociable holidays have proven hugely productive for Damian. Freed from the demands of teaching, he finds himself discovering new images, new techniques almost faster than he can throw them down on paper. Different artists thrive in different conditions. Days of swimming, playing, fishing with the children, punctuated by short bursts of activity in whatever makeshift studio space he can create, seem to work for Damian, enabling him to paint 'the Joy as it flies'.

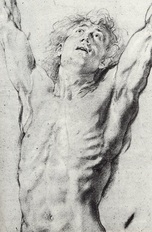

Damian paints the human figure in movement, in light. He does the occasional straight portrait, but it is an ability to capture an individual's unique posture / gesture which is his extraordinary gift , I think. The French term for 'still life' is 'nature morte'; Damian's work is, I feel, the opposite of this, it is 'life in movement' / 'nature vivante'. Light too, he loves, especially the intense light with its accompanying long shadows at the end of a Scottish summer's day. (A sunny one!) Damian paints what he loves: the Human and in painting light, perhaps the Divine?

So much for subject matter. As for style / technique - Damian is a painter's painter. The subjects of his paintings are utterly recognisable, but of the fact that you are looking at a painting and not at a photograph, there can be no doubt. Damian LOVES the alchemy of paint, the brazen mark.

Finally, this exhibition features quite a number of paintings of me. This is a more recent development in Damian's work. Perhaps because the children are leaving home, but I'm still here. It amuses, embarrasses and (I can't deny it) pleases me that he manages to use my ageing form as a springboard for paintings of... the Eternal Feminine? Happy the painter's wife whose husband is an impressionist and not a photorealist!

Ruth Callan

RSS Feed

RSS Feed